If you’re learning a foreign language, you need to memorize the numbers. There’s no other way.

When I first scanned the list of numbers in Polish, it didn’t look great.

Jeden was good. I was happy with jeden. Two syllables, five letters, easy to pronounce.

Dwa was okay. Short enough, but the pair of consonants at the beginning was tricky.

Trzy. The real problems started when I got to three!

I’ve probably said the word trzy ten thousand times, but I still can’t pronounce it correctly! I just can’t shape my vocal organs to get it out. For some reason, transitioning from the ‘t’ sound to the ‘rz’ sound is physically impossible for me. It’s probably genetic.

My phone number ends in a 3 and whenever I have to read it out loud – whether I’m ordering pizza or making an appointment – I get a little stressed halfway through. I know that soon I will have to say that horrible number and there’s a very good chance the listener won’t understand me.

It usually goes like this:

Me: zero, siedem, trzy

Listener: zero, siedem, sześć?

Me: Nie, trzy na końcu

Listener: sześć? (for some reason, when I say trzy, they hear sześć, which is ironic because I can’t pronounce sześć either! )

Me: Nie, tak jak raz-dwa-trzy

Listener: Ah, trzy!

If I count one-two… then most educated people have enough context to know that I’m trying to say ‘three’ next.

I’ve considered surgery to rebuild my mouth, tongue and jaw. But it would be expensive. Then my wife told me that when I try really hard, when I really concentrate on pronouncing the word trzy carefully and fully, I sound like someone from Kraków. Fine. I’ll take that. It is cheaper than an operation.

Cztery, pięć. Okay.

Sześć. Another horror to pronounce. Especially when you’re still worrying about trzy.

Siedem, osiem. Fine.

Dziewięć, dziesięć. Nooooo, I moaned when I first saw these words written on the page. We talking basic numbers, one to ten. They should be short and simple. The longest English numbers from one to ten are three, seven and eight. Five letters max. Eight is too many. And all those Polish sounds and weird letters. Come on! What’s more, they are too similar. Bound to lead to mistakes.

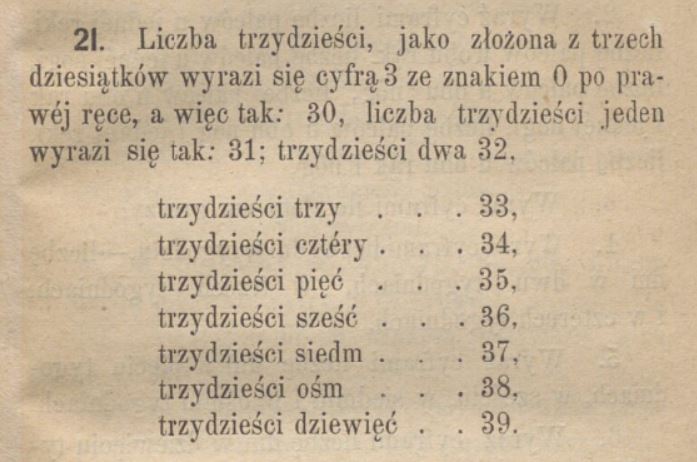

But it gets worse when you get into double figures. I had a problem remembering the difference between trzynaście and trzydzieści. Which one was 13 and which was 30? In end, and probably connected with my feelings at the time, I learned the numbers 11 to 19 by associating the ending –naście with the English word ‘nasty’. One-nasty – that was jedennaście. Two-nasty – dwanaście, three-nasty – trzynaście etc.

The worse number is 99. Dziewięćdziesiąt dziewięć. I wanted to cry.

Beside pronunciation, another issue I have is that Poles often use other forms, words or declinations to represent the numbers. Inevitably, this leads to misunderstandings with helpless foreigners. I will address the horrors of declination in the next post. But first, I’d like to devote a few paragraphs to some other complaints.

I once took part in a Polish language lesson. We had learned the basic numbers and the teacher wanted us to count to ten as a group. Jeden, dwa, trzy…and so on. So that we all started at the same time, she counted us in by saying raz dwa trzy… and everyone started counting. But I couldn’t concentrate because the whole time I was thinking ‘why did she say raz instead of jeden?’ What’s raz? Have I learned the wrong word for ‘one’?

Another time I was helping a friend to move flats. This involved carrying the sofa out of the apartment, down the stairs and into a van. As we bent to pick up the heavy sofa, getting a good grip with our hands, my Polish friend said trzy cztery and lifted his end of the sofa. My end stayed on the floor. I have never understood why Poles start from three-four and then expect action on five. In English, we start at the beginning with one-two, then lift on three. What happened to 1 and 2 in Polish? Maybe, like me, every one hates the number 3? It’s nasty.

So don’t expect any effort from me on 5. I work on 3. By the time we get to 5, I expect the job to be done!

And talking of strikes, I went through a phase of refusing to write the numeral ‘1’ in the Polish way. In English, ‘one’ is written as a single straight line, up and down. In Polish the number one consists of two lines. A diagonal line and a vertical line. Isn’t this inconsistent? Shouldn’t ‘one’ be represented by one line? Not two. It took me a while to get used to this. In fact, I rebelled at first. For geometrical reasons. Call me a purist, but ‘one’ should written in one stroke!

Then there’s jedynka. Or jedeneczka. I once entered a lift, quickly followed by an elegant-looking women, who saw me reach for the floor buttons and just said jedynka. Clearly, she was asking me to push a button for her. But which one? The building had twelve floors and I had heard ‘jed something‘, but it wasn’t exactly jeden or jedenaście. Did she want me to push ‘one’ or ‘one-nasty’? Because I dithered for so long and because the lift had already left the ground floor, she quickly reached out and pressed the number one. If she hadn’t reacted, she would have ridden with me to the 8th floor while cursing me for being a dumb foreigner who couldn’t work an elevator.

I used to watch Szansa na Sukces, not because I enjoyed the singing, but because every time they chose a number at random by pulling on a string, they would announce it using a diminutive – dwójka, piąteczka… my favourite was always czwóreczka. I’ve never understood how a number can have a diminutive form. One is one. Mathematically. How can you have a little one? If jeden plus jeden is dwa, how much is jedynka plus jedynka? Less then two, surely!

Perhaps, I’m splitting hairs?

Incidentally, in Polish ‘to split hairs’ is dzielenie włosa na czworo. In English, when we split hairs, it’s just into two parts. Four is very, very precise. Almost sub-atomic. What technology do Poles use to split hairs this finely?

Finally, let’s move on to the big numbers.

I always thought that the big numbers in English were easy. As we add three zeros, we simply change the first letter(s) – million, billion, trillion. According to the American comedian, Rich Hall, the next number after trillion is a ‘killion’ – because if you try to count up to a killion, you will die before you get there!

Then I started learning Polish. Here, the big numbers are milion, miliard and bilion. That’s confusing, was my initial reaction. I always got mixed up when I saw miliard. I thought it was the Polish word for million. It just looks like it should mean a thousand thousand. But then I discovered that we used to use milliard in English. To mean… well, a billion. But the American billion, not the old British billion. The old British billion is equivalent to the Polish… bilion.

Confused? Just try counting to a killion. It’s easier. Raz, dwa, trzy… What would be the Polish for a ‘killion’, anyway? Zgilion, combining zginąć and milion, I guess.

Last month I was in a shop, paying in cash at the checkout. The shop assistant pointed towards my wallet and said czy chce się pan pozbyć tego bilonu? I had no idea what he was talking about. But I heard the word bilion. What billion? Is he suggesting I am carrying a billion zloties in my wallet? Unlikely. And even if I were, I wouldn’t be in a hurry to get rid of it. And not in Carrefour Express.

He repeated the question two more times, using the same word. He obviously didn’t know any synonyms.

I eventually realised that he was referring to loose change. My wallet was bulging that day, not with a billion in cash, but with lots of small coins. So I swapped some for a ten zloty note.

That’s the beauty of language learning. I’ve been asked for drobne or końcówka (change) a million times in Polish shops. I even wrote a post about it. But on the 1,000,001th occasion, the cashier used a different word. And to make matters worse, it just happens to be a false friend!

Anyway, I’ve decided to write a book, offering financial advice in a self-help style. The title will ‘How I Lost My First Billion‘. Please don’t spoil the content (the above anecdote). There are so many suckers out there. I’m pretty sure I can sell a zgilion copies.

images from Plakat: Poznaj Polskę w liczbach [1945], Nauka rachunków. Cztery działania z liczbami całkowitemi (1883). Wyd 2., Warszawa: Lesman i Swiszczowski, Przyjaciel Domowy: pismo dla ludu, 1852, R.2, nr 2